"This is Culturally Inappropriate"

How the Clipse's triumphant return creates room for a genre, and it's torchbearers to grow. "Let God Sort Em Out" and its accompanying rollout draw a line in the sand.

I’m beginning this with a public service announcement:

As a writer, I seek to be understood and judged by the final version of the work. Unfortunately, in many cases, the work is published and I immediately learn it was released one (or a few) edits too soon.

When this happens, I race back to the site and promptly make the appropriate changes. Changes that are never reflected if you only read these pieces as emails.

Please consider downloading (and using) the free Substack app. The app also features an audio player, meaning pieces can be read to you. It’s also a great avenue to find other writers you may resonate with, or share your own thoughts.

Thanks, now to the reason you’re here.

Last September, in a far too familiar moment of loss, frustration and mourning, I wrote about our legends’ inability to grow old. It was on the heels of learning that FatMan Scoop, after being rushed offstage during a show in Connecticut, lost his life. In the piece, titled “Get Rich [and] Die Trying,” I spoke about the ways losing our cultural tastemakers, translators of urban experiences is a disservice to those that follow.

I also provided a list of Black, male rappers/entertainers/actors, all stuck down way too soon, and in many cases preventably. This has left a deep chasm, a foundation unable to be laid; while rap has matured beyond its infancy phase, it’s been largely denied the opportunity to evolve past young adulthood. We’ve long endured a state of arrested development, our artists passing at early ages has kept Hip-Hop branded as a young man’s sport.

This piece feels like the antithesis of that.

Watching Clipse return to the main stream, seeing them deliver a highly anticipated album and a flawless promotional rollout, hearing an album that satisfies on every listen is edifying. It deepens the line in the sand drawn by an elite group of grizzled veterans, artists who in a sea of melodic mumble raps are determined to enunciate their way back into our hearts.

To be clear, this is not an album review. The album is great, all thirteen tracks move you through waves of emotions. It begins with the pair navigating the loss of their parents, transitioning to firmly dealing with conflict, and like all Clipse albums they delve into the nuances of drug trafficking (a multigenerational endeavor, firmly in their rear view). Malice and Pusha T bounce well off each other seamlessly etching together stories about escaping poverty, sustained opulence, sacrifice, losing folks to the penal system, the role religion plays in their lives, and successfully returning fifteen years later with the circle you started with. Social media driven concepts like “clout,” “chart numbers,” or “aura farming,” never come up. It’s refreshing that way.

Maybe this was a review.

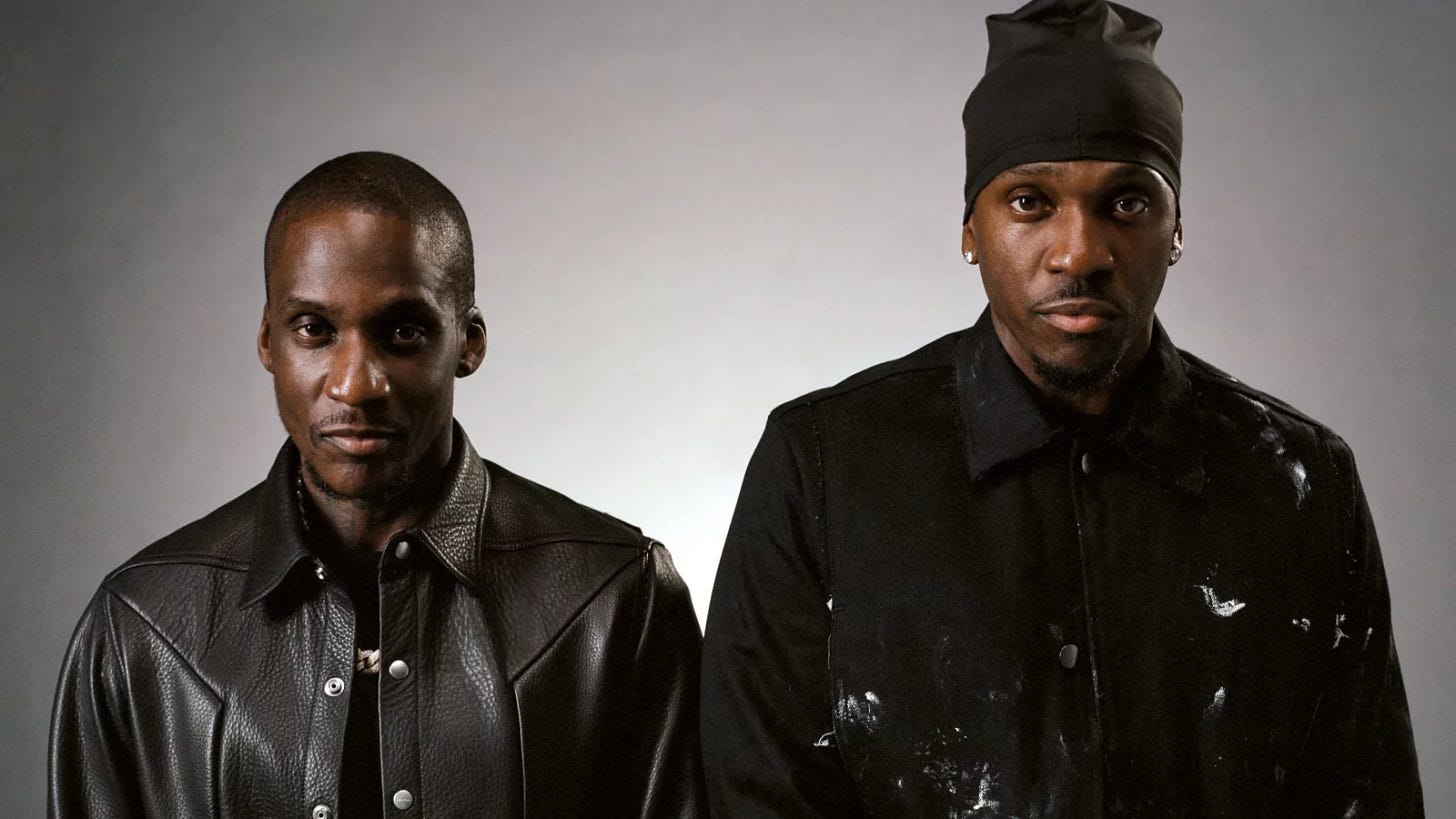

For the uninitiated, Clipse is a duo of brothers Malice (52) and Pusha T (48). Hailing from Virginia, they jettisoned into our consciousness in 2002 on The Neptune’s percussive masterpiece “Grindin'.” I was a high school senior at the time and can assure you that short of the “duck and cover” era, this would begin the most hazardous time for lunch tables across the country.

Clipse would build momentum, featuring on Justin Timberlake’s solo debut “Like I Love You.” This created unimaginable anticipation for Lord Willin’, their own debut album, released that same summer.

In 2002, Malice described the brothers’ individual characteristics as follows:

"Malice, he think he hard, tough guy of the clique

And Pusha, he walk around like he swear he the sh*t"

You right on both counts… Clipse is us.

These days, they’re being compared to “The Wire’s” Brother Mouzone and Omar, aligned in purpose. Malice on a mission to share perspective gained as he’s grown in his faith, Pusha determined to prove that they’re still the best at this. Frankly, he’s right and skill-wise it feels like no time has passed. Pharrell sounds invigorated behind the boards, crafting beats reminiscent of Pusha’s It’s Almost Dry run. If you know Skateboard P solely as the guy from the Lego movie who sings “Happy,” this turn may feel menacing. For everyone else its delightfully familiar, there’s a grittiness in his catalog only the Clipse can inspire.

The duo would release two other albums, Hell Hath No Fury and Til The Casket Drops, along with a series of mixtapes (as Clipse or Re-Up Gang). However, in 2010, a drug trafficking conviction involving their former manager would prompt Malice to leave the group. Pusha T would begin working with a (then) far less problematic Kanye West, helping to pen many of his hits and running West’s G.O.O.D. Music imprint. He’d also carve out his own successful career releasing five critically acclaimed solo albums. Like Bun B, during Pimp C’s absence, Push’ individually kept the brand alive and in popular demand.

Malice (rebranded as No Malice) would release two albums with the same brand of piercing lyrics, but little fanfare. We’ve always had a complicated relationship with sanctified rap songs. A conversation with his dying father (a deacon), along with Pusha’s well timed invitations to collaborate brought Malice back.

In an industry that trends towards the transactional or trendy, there’s refreshing wholesomeness to making it big with the ones you came in with. Malice, Pusha and Pharrell consistently embody this.

their collaborations began in the 90s, creating music at Chad Hugo’s house.

by 2009 they’d create stellar albums together

it shows up again in 2018, at Pusha’s wedding. With Malice serving as officiant while Pharrell assumed the role of Best Man.

and in 2025, after a two year recording process, as they gift us with one of the most important albums in recent memory Let God Sort Em Out.

There’s a very strong emphasis on the strength of the collective, believing in the brand, loyalty, and standing for something… even if it costs seven million dollars and a Def Jam record deal. We say “it’s the principle of the thing” a lot, but how many artists do we currently see living by this credo?

Why is any of this important?

This album release sits with the backdrop of Sean Combs currently awaiting sentencing on Federal charges for counts of prostitution. Charges that feel insufficient based on testimony and a heinous leaked video. This presents as a necessary juxtaposition solely because as a music fan freshly in his forties; it’s impossible to speak about my understanding of rap music without thinking of who brought us to the party (hypothetically).

Biggie lyrics forged my earliest fascinations with rap music, though it’s fair to assume the connection would be inevitable. The music and I share similar Jamaican roots. This is where I remind you all that DJ Kool Herc, a Jamaican immigrant living in the Bronx gave the music a starting point. An artform pulling from the legacy of people skanking in the streets, under towering walls of speakers. Herc brought Jamaican Sound system culture and toasting to the masses hosting a back-to-school Jam on August 11th, 1973. This changed the sound of the world forever.

I remember being enamored by the “Mo Money, Mo Problems” video, being transfixed in time as Biggie brought us “Juicy,” my first time experiencing a rags to riches anthem. Visiting cousins in Queens the summer Junior Mafia’s “Crush on You” gained traction. Bad Boy Records was cranking out hits, and their lyrics were swiftly being immortalized in my hard covered notebooks. Pro tip: jotting down your favorite artists’ lyrics not only helps you to absorb and remember them, it’s a cool way to practice penmanship.

I’d continue being a fan of rap music for well over thirty years, and it’s been great watching the recent evolution into a genre that allows room for growth. It’s transitioning into a space that celebrates older men who’ve learned to lay their vocals and go home. Artists who know when to leave the party and comfortably stay out of the mix. It allows artists a longer runway, where “aging out” no longer feels like a valid concern.

In spaces where older voices are appreciated, audiences are blessed with richer storytelling - we’re all better for it. Watching the Clipse’s mastery of time gives us notice that [our OGs] got something to say. “Best Rap Album” GRAMMY wins for Nas and Killer Mike (47 and 49 respectively) affirm the sheer brilliance of their offerings. When artists are allowed to develop and grow, they forge cultural landmarks for a generation who’s musical heroes died violently in their 20s.

When rappers are allowed to grow up:

We get to see our music elect presidents.

Artists, who have always excelled at voicing community concerns, move into roles as community organizers or activists.

Artists model ways to resolve marital issues in ten, well-sequenced tracks.

They put their money to work, as venture capitalists, helping to launch Black-owned start-ups like Bevel.

The wisdom transferred through rap music meanders onto new real estate, in college classrooms. As several current and former artists have taken on careers in higher education.

Musicians become health influencers; in the gym, or at any of Styles P and Jadakiss’ Juices For Life locations.

In an artform that long celebrated her pioneers rhyming about the things they’d die for, it’s beautiful seeing what they are currently living for.